The Roots of Violence in the West Bank

Unraveling the history of the West Bank (and the Oslo Accords) to reveal the utter simplicity of the occupation

There is a common exchange between the critic and supporter of Israel that goes something like this:

Critic: Israel has been displacing, oppressing, and killing Palestinians for 75 years.

Supporter: It’s much more complicated than that.

Critic: Actually, it’s not very complicated at all.

I’ve come to believe the truth is somewhere in between: to understand just how simple the occupation is, it helps to first understand its complexity.

Zionists took most of what we now call Israel by force and UN Resolution in 1948, but East Jerusalem and the West Bank—which refers to the west bank of the Jordan River—remained under Jordanian control (and the Gaza Strip under Egyptian) until the 1967 Arab-Israeli War when Israel defeated a coalition of Arab States in six days.1

For the purposes of this argument, I’m going to stipulate that everything that happened between 1948 and 1967 was legitimate. People (and countries) fight wars, they say, and the winners claim new land. Even within this framing, though, there are, actually, rules: the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 had made it illegal for an occupying power to transfer parts of its own population into its occupied territory.

But in 1967, before the blood-soaked ground could dry, young Israelis had demolished 160 homes near East Jerusalem, expelled over 6,000 residents, and begun construction on the first settlement. (Demolitions started hours after the end of the war, a fact that evokes the rabid excitement of some in Israel to resettle Gaza.) This continued for decades, and by the mid-90s, the population of illegal Jewish settlers had risen to 250,000 among 1.5 million Palestinians.

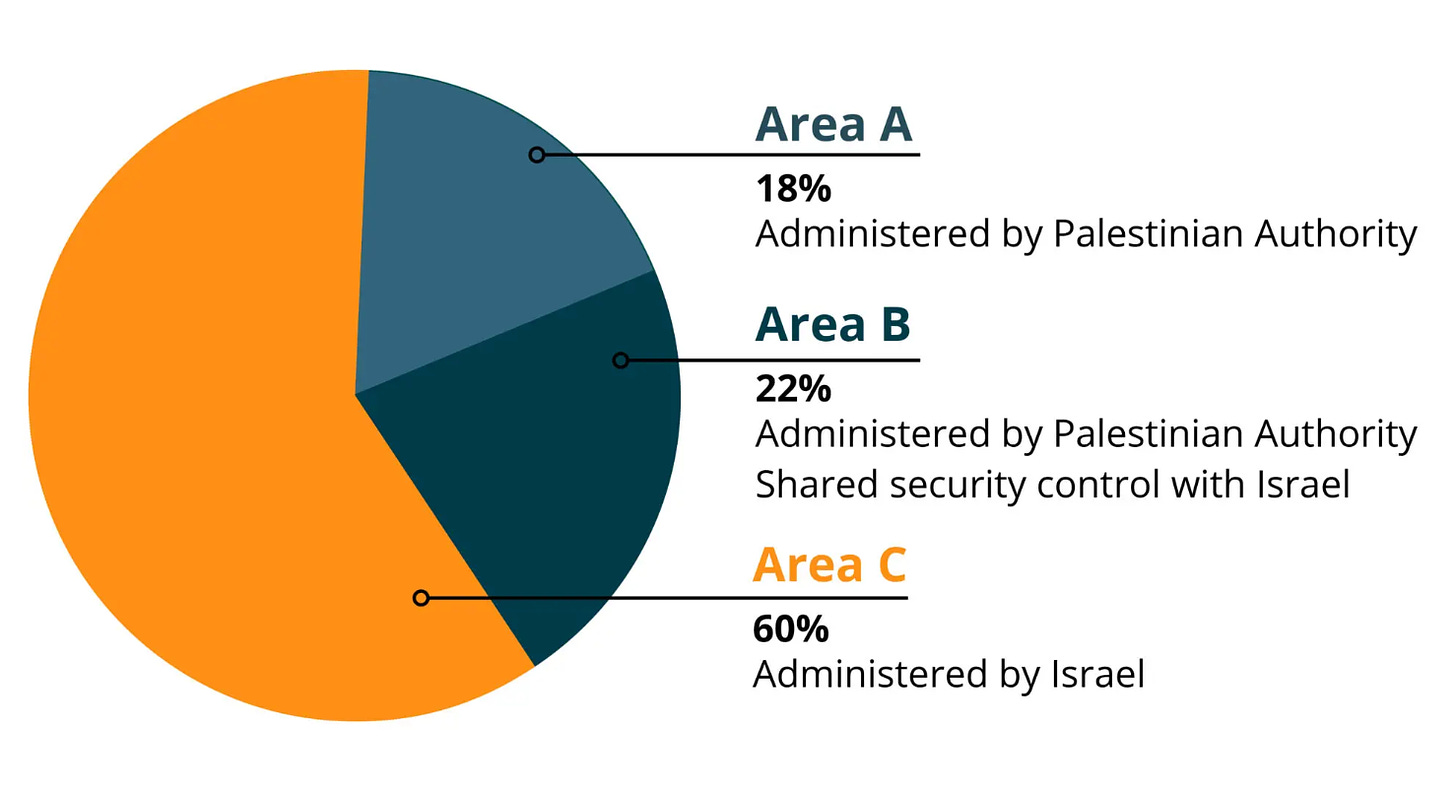

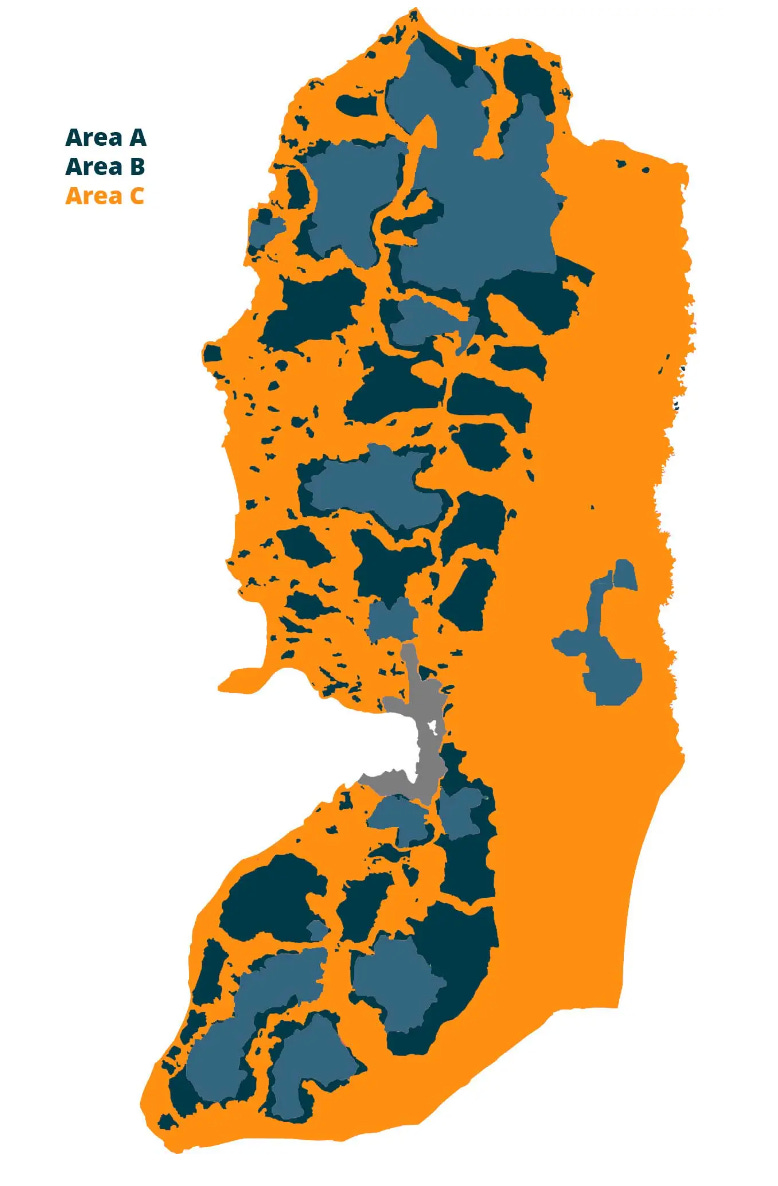

Palestinians resisted being thrown from their own land, and violence was widespread (the uprising beginning in 1987 became known as the first intifada). In 1993, secret talks opened up between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). This resulted in the signing of the Oslo Accords, which attempted to create peace through mutual statehood recognition2—a monumental but doomed gesture immortalized by a famous White House handshake between longtime adversaries Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO leader Yasser Arafat—and by splitting the West Bank into Areas A, B, and C. Across these territories, administrative and security control would be distributed between Israel and Palestine.

Israel secured what it wanted, and Palestine was left to maintain partial authority over a scatter plot of islands in a sea of newly-minted Israeli-controlled land.3

This is where the complicated story becomes very simple: from the day the Oslo Accords were signed, Israeli settlers disregarded the boundaries and continued building settlements on land that was not theirs even under the new standards negotiated by their own government. In fact, none of the land was theirs: the Accords granted Israel administrative and security control of some land but ownership over none, meaning all West Bank settlements remained illegal. The rate of settlement building tripled between 1993 and 2000, leading to another mass Palestinian uprising (the second intifada, infamous for the dramatic spike in suicide bombings) and a brutal Israeli crackdown. And yet, despite the blatant Israeli provocations and refusal to honor the boundaries, the familiar refrain remains: “Palestinians never gave peace a chance after the Oslo Accords.”4

Israel’s (territorial) goalposts have never stopped moving. Current estimates place the West Bank and East Jerusalem population numbers at 750,000 settlers and 3 million Palestinians, but the settler population continues to grow; Israel just announced a plan to build 3,000 new settlement housing units near the site of a “Palestinian shooting attack.”5 US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken expressed his disappointment in this decision, referring to the new settlements as illegal under international law while leaving out the fact that the old settlements are illegal as well.

Blinken’s toothless condemnation brings to mind the tendency among modern-day liberal Zionists to caveat their support for Israel with a disclaimer that they do not support the settlers. This makes it sound as if the settler movement is a far-right side project, but settling the West Bank has been central to the State of Israel’s goals since 1967 (or before, really). Even Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s most left-wing Prime Minister who was assassinated by a far-right extremist for signing the Oslo Accords, stopped well short of supporting the withdrawal of illegal Israeli settlers from the West Bank (and as Defense Minister, he encouraged soldiers to “break the bones” of Palestinians who resisted). And again, even with Rabin’s ostensible disapproval, the building of new settlements never stopped, foreclosing any opportunity for a true two-state solution.

But if, after all that, one still insists on thinking of the settlements as a side project, perhaps it’s helpful to consider the issue from the other side: the West Bank is where the largest population of Palestinians anywhere in the world has been fighting against land theft since 1967. For Palestinians today, resisting settlements is not only central—it’s most of what’s left of their statehood project.

One final point: the Oslo boundary lines don’t just separate Palestinian villages from Israeli settlements—they run straight through many villages, interfering with daily life and making urban planning a nightmare. Palestinians are forbidden from building schools, hospitals, homes, etc., on any land within Area C, but the disruption goes beyond these lines: the Oslo Accords’ designation of Palestinian authority in Areas A and B has never stopped settlers and soldiers from intruding on, destroying, and stealing private land. Ask any Palestinian, and they will laugh at the notion that they control a single square meter of the West Bank—anytime (and anywhere) Israel wants to assert its dominance, it does.

This is the story across all of the West Bank: every day, Israel tears through the paper-thin rules that were crafted to sustain the illusion of shared governance. The violent occupation rules all the land, and it has since 1967.

The war officially kicked off with Israel’s massive surprise attack on Egypt’s air force, though many historians have long claimed that it was a preemptive strike for defensive purposes. I am not qualified to judge.

Since the term has become so politicized, I should also clarify that I am using “Zionists” here in its literal sense, referring to members of the Jewish nationalist movement who sought to create a Jewish state in historic Palestine.

“Mutual statehood recognition” is not entirely accurate, actually: the PLO recognized the existence of the State of Israel, while Israel only recognized the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.

There is no historical consensus on why Arafat agreed to these terms, though I tend to accept the perspective that the PLO was desperate for an end to the occupation and a shot at statehood of any kind.

There were, of course, several other incidents that led to the second intifada. The single biggest escalation occurred on February 25th, 1994, when a Brooklyn Jew turned Israeli settler named Baruch Goldstein walked into the Cave of the Patriarchs mosque in Hebron with an assault rifle and sprayed bullets, killing 29 worshippers and wounding 125 others before a fatally injured man beat him to death with a fire extinguisher. Palestinians rioted, and Israel’s violent military response led to the additional deaths of 25 Palestinians and five Israelis. In the immediate aftermath, the government imposed a two-week curfew on the 120,000 Palestinian residents of Hebron, while the 400 Jewish settlers were able to continue roaming freely (Hebron is the occupation-ravaged city that I walked through in You Don’t Understand How Bad It Is Here). To this day, many far-right Israelis continue to celebrate Goldstein as a national hero (including National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, who kept a portrait of Goldstein on his wall until 2020). Just under two years later, another far-right Israeli, Yigal Amir, assassinated Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin during a rally to support the Oslo Accords.

Given that most Palestinian violence in the West Bank is explicitly in response to settlements, this is certainly an odd tactic to lower the temperature—to say nothing of Israel restricting access to the Al-Aqsa Mosque during Ramadan.

We have always shaken our heads and shrugged, " There will never be peace in the Middle East". This wonderful article explains why. I have restacked.

The clearest statement of the facts that I have seen (partly because you have used the footnotes so well). Many, many thanks.