Redemption

The Kenyan coast, Uganda and Zimbabwe; final reflections with Simone Weil. (Africa pt. 7)

“Man only escapes from the laws of this world in lightning flashes. Instants when everything stands still, instants of contemplation, of pure intuition, of mental void, of acceptance of the moral void. It is through such instants that he is capable of the supernatural.” —Simone Weil

At the top of my notes for this piece, the last in this series about my trip to Africa, are the words New Beginning. I have no recollection of writing them.

New beginning? Ugh. It’s so reductive. And how gauche to declare a new beginning roughly eight weeks after doing just that. I am tired of hearing myself talk about my life in this way.

But I’d misread the note. It was actually just a straightforward reminder to write a new beginning to this piece, because the one I’d already written was both reductive and gauche: the story of a new beginning without using those words. I fear this urge to interpret may be obscuring what’s real.

Goodbye to all that.

Life is an ongoing reflective experiment. A perpetual cycle of action and introspection with as many false starts as real ones. To the extent that a moment may be pregnant with meaning, we can’t begin to understand it.

Sometimes the void is better left unfilled. Only then can the truth seep in.

Nora: In a lot of your writing from Africa it seems that you aim to seek redemption in order to negotiate certain tensions with your own actions. In some instances I think you do this by fully disclosing your own meta-discourse to your interlocutors. This passage is an example:

“How do you feel when you see white people like me being taken on tours of Kibera?” I asked.

“I feel fine about it,” Ricky said. “I’m not ashamed of how I live. I’m glad you want to see it.”

I told them about the psychic baggage I’d brought to Africa: the white savior complex, story extraction, treating the continent as a place to cure my boredom.

“It seems like you think about this stuff a lot more than we do,” Ricky said.

“I think you’re right,” I said.

You are seeking approval that it is okay to visit Kibera. If a local says it's okay, it must be true. Now you can feel better.

I had a similar feeling when you talked about your first meeting with your friends in Nairobi. At first, you felt uncomfortable, then you overshared your concerns, and they relieved you by comforting you in your insecurities. Maybe that's how it should be in communities. But intellectually, and from a writing perspective, it feels like a shortcut.

Me: I agree I am looking for the redemptive angle but I’ve tried to make it clear in my writing that I’ve not actually found it—like ending the piece about gays in Africa with the rainbow at Victoria Falls. I hope it was obvious that I was admitting to taking the easy way out by dodging the question of whether or not I’d be back.

In terms of the locals telling me to stop worrying about white saviorism, I agree, I don’t know what to make of it. It’s confusing. Frankly it would be easier from a writing perspective if they validated my concerns. Instead they force me to rethink everything I’ve said about the ethical concerns surrounding my trip to Africa. They force me to question my intellectualization of everything.

Nora: You are trying to make sense of why they might pretend that it’s okay to have certain behaviors as a white person?

Me: I don’t think they’re pretending. I think they literally don’t care about “white saviorism” the way you or I do. Which forces me to wonder if (1) they are just naive or (2) I am over-intellectualizing.

Yes, their validation of the motives behind my trip it makes it more ethically acceptable that I am here, but it ties me up in knots intellectually. To me, this is even worse. It’s like when you confront a friend or a partner with a problem you’ve been having with them, and they tell you “you’re just overthinking it.” Who wants to hear that?

Nora: I definitely do not think they’re being naive.

Me: So you think they’re lying to me? I think they are being nice but I don’t think they’re lying. I think they are much more concerned with their day-to-day welfare than they are about these grand narratives around the system. But you think they’re lying?

Nora: Not necessarily. I do think that they are not entirely honest because people are usually kind and sometimes opportunistic. So to a certain extent, they will give you what you want to hear since your experience is in direct correlation to their benefit. I agree that they do not over-intellectualize these dynamics to the same extent, but just because they do not use the same vocabulary does not mean that they don’t feel or think similarly to you or me.

Me: Hmm. Okay.

That sounds like it could be right.

Nora: Or maybe not! I’m not the authority.

Me: You’ll be the first to know once I find out for sure.

Nora: Great. Do you have an ETA?

Me: Should be any day now.

And redemption will follow shortly after that.

“So far as one has only an idea, one has nothing that’s real. The great human error is to reason in place of finding out.” —Simone Weil

I nearly missed my flight after drinks with the Kibera boys. We ordered chicken wings and they took a long time to come out and then I wanted just one more beer before getting back on the road. I forgot about Nairobi’s paralyzing traffic. I prayed to God from the backseat of that Uber before arriving at NBO 40 minutes before departure and setting a new land speed record running from security to my gate. A very nice Kenya Airways gate agent named Lydia let me onto the plane at an unreasonably late stage in the takeoff process.

So I flew to Mombasa, the sparkling blue and white city along Kenya’s southeast coast. The region is one of the country’s most culturally diverse for reasons that become obvious when you understand its history.

Mombasa was founded by Arabs in 900 AD and built into an invaluable port for the intra and inter-continental Indian Ocean trade of spices, gold, ivory and slaves. The Portuguese showed up in the 15th century and decided they’d like to have it for themselves, so they sacked Mombasa and ruled over it for about 100 years until Oman laid siege and took control. The strategically located city changed hands over and over until it wound up with the British who kept it until 1963 when all of Kenya was granted its independence.

The ground here must be soaked in blood, but today, in Mombasa, people hang out. They hang out and drink coffee on the stone steps by the water. They hang out and chew sugarcane on Makadara Road. They hang out and eat cassava crisps at the Mama Ngina waterfront. The Bantus and the Swahilis and the Kenyan Arabs are all hanging out. The shawarma vendors and the tuk-tuk drivers, the chip fryers and the chai guys, the cats and the tourists—they’re all hanging out.

“It’s a Wednesday afternoon,” I said. “No work. No school. Nobody’s making deals out here. Everyone’s really just hanging out.”

“Well,” said Kioni. “I think they value time a little differently than you do.”

We were sitting and drinking kahawa—Swahili for coffee—on those stone steps by the ocean in Old Town. The coffee stand looks impromptu but apparently it’s been around for generations. Three tin kettles sit on a charcoal stove on a large cement block. Two men pour the drinks into small glasses and colorful tea cups and hand them out for the equivalent of fifty US cents. You have three options: kahawa chungu (bitter coffee), kahawa tamu (sweet coffee), or chai. There is no milk and no sugar. A young boy wanders the crowd and sells sweet biscuits baked by his mom and wrapped in the day’s newspaper. Dozens of people were out, standing in small circles, leaning against the steps, sitting on large rocks and lounging on their sides. We had joined them to hang out for the second straight day, because that’s what one does in Mombasa.

“I value time,” I said. “You know what they say where I’m from: ‘Time is money.’”

“Sure,” Kioni said. “If you’re fighting to survive. But we’re not talking about your friends in Kibera.”

“I know,” I said. “That’s different. I’m talking about the professional class of New York. We never shut up about the value of time. There’s this expression: ‘There’s no such thing as a free lunch.’”

“No?”

“While you’re eating that ‘free’ lunch, somebody else is out taking what could be yours.”

“Oh dear,” she said. “What a way to live.”

“It’s awful,” I said. “What is time to you?”

“Also invaluable,” she said. “But not because it translates to money. For those of us fortunate to have an excess of it, time is valuable to the extent it can be used to facilitate leisure, passion and connection.”

“Hm.”

“And in that sense,” she said, gesturing out towards the languorous crowd, “All of us here are being very efficient with our time.”

The previous morning, Kioni, Amara and I had all met in the garden of the Airbnb in which we each had a room, just across the bay from Fort Jesus. Each of us had traveled alone to Mombasa to recharge our batteries, and fate had brought us together for two days of vigorous hanging out.

I’d been under the gazebo drinking coffee and eating breakfast. A family of velvet monkeys was harassing me for my toast with butter and strawberry marmalade when a dragon walked by and scared the shit out of all of us. The monkeys actually screamed. I guess it was technically a monitor lizard but aesthetically speaking it was a small dragon. We all scattered.

Amara and Kioni were on the bench by the pool. Strangers to me, at that point. They were chit chatting. I was jealous, I wanted to chit chat, so I walked over and introduced myself.

“There’s a dragon over there,” I said. “So I’m going to sit here with you if that’s all right. I’m Jasper, by the way.”

Something just clicked and the chit chat escalated. Nobody had any plans for the day, so we decided to hang out.

Kioni is from Western Kenya. She’d studied to become a nun until getting cold feet and bailing at 17. Now she’s a devoted educator, a globetrotting literature teacher getting ready for a move from Kenya to Singapore. Amara is from Adis Ababa, Ethiopia. She still lives there now, studying and working in governance, fighting to make Ethiopia a more inclusive place for all. Things in her country were not going so well, and she’d been feeling an increasing sense of despair.

We went out for lunch at a Mediterranean restaurant. The faded, kitschy music from the Barbie movie was bleeding out of the empty theater next door. I had some vague notion that a Barbie discourse was tearing through my cultural milieu back home. I was living in a different universe.

I told them what had been on my mind of late.

“I’ve been in Kenya for two weeks,” I said. “I’ve asked anybody who would listen. And I can’t find a single person who expresses resentment towards the West.”

“Your heart is really set on finding somebody to hate you, isn’t it?” Amara asked.

“I’m just confused,” I said. “What happened to the wretched of the earth? What happened to decolonization at all costs?”

“What happened to the beach?” she said. “I thought we were going to the beach.”

“Fine,” I said. “Let’s go.”

We ordered the check.

“The answers to your questions are not so simple,” she said.

We walked to the beach. Amara and I drank gin and tonics. Kioni drank an iced tea. A woman tried to sell me a sundress for my wife back home. My wife happens to hate sundresses.

“I think you may be forgetting about the most virulent aspect of colonialism,” Kioni said.

“What’s that?”

“The colonization of the mind. One hundred years of British indoctrination. Entire precolonial histories and cultures wiped out.”

“Hm.”

“Many Africans still live with the unconscious impression that there is something inherently superior about the West.”

“Most people I’ve talked to frame it as a practical decision,” I said. “They know the history, but they’re too concerned with their day-to-day lives to harbor any resentment.”

“I’m sure that their practicality provides a superficial contentment,” Kioni said. “But it’s a false consciousness. They won’t experience true happiness until they’re free from their internalized inferiority.”

“And this freedom and happiness,” I said. “It takes the form of bitterness?”

“That’s just a product of a deeper awareness of the lasting effects of colonialism,” Kioni said. “That awareness is where the salvation comes from.”

I realized I was late for a food tour I’d signed up for. Kioni and Amara decided to come along. We hopped in a tuk-tuk and sped over to Old Town where we met our guide Joan. The first stop was English Garden for kahawa.

“How exactly does this deeper awareness form?” I asked.

Kioni nodded towards a group of young people. “It starts right there.”

“What do you mean?”

“Through education.”

“And is it happening?”

“It’s hard to say. The Kenyan education system still has an overwhelming British influence. It’s really not our history they’re teaching.”

We tried the sweet coffee, the bitter coffee, and the chai. A lot of caffeine to be drinking as the sun was going down.

“And it gets more difficult from there,” Kioni said. “You’re right that it’s not easy to create a deeper awareness when people can’t afford to buy gas.”

“And that’s the irony of it,” Amara said. “Colonialism created the conditions that obscure the fact that it was colonialism that created those very conditions.”

“That’s right,” said Kioni.

“Imagine, all of Africa’s top resources and energy were directed towards Europe for the better part of a century,” said Amara. “What do you think happened here? The entire continent’s development was stunted. We’ve never recovered.”

We walked to Makadara Road to meet Ahmed the shawarma guy. A real showman. He pointed to his giant spinning rotisserie and performed a little jingle.

“If you don’t know, get to know. Taste it to believe it, you’ll never regret it. The best shawarma in East Africa, I guarantee it.”

He shaved off slices of juicy chicken and handed them out. I tasted it, I believed it, and I have no regrets. Joan told us later that he’d won a big grilling competition in Zanzibar. He was known locally for feeding the needy.

“Okay,” I said. “You’re right. Colonialism, neocolonialism, capitalism—the gifts that keep on giving. Even President Ruto with his whole ‘hustler nation’ shtick. It’s pure cultural hegemony. He makes it all about the individual, so people can’t see how the system exploits them. I know the playbook well, they use the same one back home. But this is exactly the thing I’m struggling with. All of this suggests that I’m in a better position to know what’s really going on than the people who are actually living it. I’m intellectualizing my way out of taking their words at face value.”

“You poor guy,” Amara said. “You’re looking for a clear answer that doesn’t exist.”

We stopped by a sugarcane stand. A man with large biceps turned the wheel of the steel press with one hand while passing through the thick shoots with the other. He worked quickly. A murky green juice poured into plastic cups. I was afraid it might be too sweet, but it was actually quite understated: tangy and floral with notes of honey. A group of children gathered around hoping to get our leftovers. We each drank half a cup and then gave the rest to the kids.

“Like this ‘white savior’ business you keep talking about,” Amara said. “Of course it’s real. Of course it’s problematic. To a certain extent, the bad optics are unavoidable—somebody will see what you’re doing and walk away with the misguided impression that the benevolent white man has come to save the helpless Africans. Maybe your writing or photographs will contribute to that. But I’m sure you’re doing good work here. I’m sure people have benefited, yourself included. All of these things can be true.”

“And now we have met and become friends,” Kioni said. “Here we are having this great conversation. There is inherent value in that.”

“Right” I said. “So the question is whether my presence here is a net positive or a net negative.”

“Are you under the impression that this is a solvable mathematical equation?” Amara said. “Once again, it’s not so simple. Your worldview doesn’t have to be wiped clean every time somebody contradicts something you’ve read in a book. You’re adding layers and nuance to it.”

We walked to the Mama Ngina Waterfront. The sky was midnight grey. The full moon reflected off the black sea. A street vendor peeled slices of cassava directly into a vat of boiling oil and then brought them to us in a wood bowl. He poked holes in coconuts and passed them around with straws.

“Look,” I said. “All of this goes way beyond Africa. It raises some difficult questions about my life back home. I read a lot of books. I talk to smart people about those books. We’re all very progressive and we want to live in a world that’s more just.”

“God bless you,” Kioni said. “God bless America.”

“Shush,” I said. “I’m not done. My point is that my peers and I, for the most part, are not of the underclasses that we claim to speak for. There’s a huge disconnect there.”

I scalded my mouth on a fistful of cassava crisps. I’d already finished my coconut so Amara passed me hers. I took a sip.

“Thank you,” I said. “Earlier you jokingly said ‘you’re really looking for somebody to hate you,’ but there’s a truth in there, because the world that I advocate for is very different from the one that I enjoy the privileges of, and derive my cultural sensibilities from.”1

“I understand,” Amara said. “We’re all going to have to make some sacrifices when the revolution comes.”

I laughed.

“And on what you’ve heard here,” Kioni said. “I wouldn’t expect every Kenyan you meet to share their true feelings about the West with you. You are, after all, very conspicuously from the West.”

“What gave it away?”

“You’re white.”

“I was being sarcastic.”

“Exactly. You’re white and sarcastic, so you are from the West.”

“Right.”

“So I don’t care what the Black Kenyans have told you. The generational trauma is there. The longing to get their land back is there. Maybe it doesn’t present itself in the way you’d expect it to, but trust me, it’s there.”

We went out for drinks and then called an Uber back to our Airbnb. I couldn’t believe the car that showed up.

Our driver’s name was Lennin. His dog’s name was Trotsky. I asked him how many communists he knew in Mombasa.

“There’s a few of us,” he said.

“And what do you do?”

“We read books together. We talk about the issues of the day.”

“What are the issues of the day?”

“Well,” he said. “Our culture is changing from the old, Swahili way of life, which is slower and based on shared values, to something much faster and more about individuality.”

“It feels pretty slow to me.”

“Not how it once was.”

“So are you working on the revolution?”

He laughed. “No. We just make things more fair where we can. Society rejoices in achieving through hook or crook, so we support one another and try to achieve in an honest way.”

“How’s that going for you?”

We pulled into the driveway of our Airbnb. He put the car in park, stared at his hands for a few seconds, and then turned to look at me. It was the first time I’d seen his eyes. They were full of warmth.

“It has become increasingly important to practice patience.”

Joan told me that before leaving Mombasa I’d need to visit a place called Swahilipot Hub.

“It’s down a long dirt path past the butterfly house by the sea,” she said.

“Okay,” I said. “What is it?”

“You’ll see.”

There it was down the long dirt path past the butterfly house by the sea, a small champagne-colored castle sitting on an enormous plot of grass. I met Nicole, the director of the space.

“So what exactly do you do here?” I asked.

“Sanaa.”

“What is sanaa?”

She pointed to a group of writers on the veranda under a thatched roof. “That is sanaa.”

“Writing?”

She pointed to a painter with an easel set up by the amphitheater. “That is sanaa.”

“Painting?”

She pointed to the shimmering reflection of the sun on the sea. “And that is sanaa.”

“Hm.”

“You don’t have a word for it in your language,” she said. “Google will tell you that it translates to ‘art,’ but it’s much more than that. Sanaa is all of these things. This is what we do here.”

I think I understood. She took me into a conference room where a group of writers was waiting for me. “We heard you like to write,” one of them said.

So we wrote.

I walked to English Garden to meet Amara and Kioni for more coffee and chat. We talked about time. What it means, what it’s for. We had lots of time that day, and we used it wisely. We wandered aimlessly, we met local characters, we drank sweet drinks and ate savory food. Something very special can happen when kindred spirits meet by chance in a foreign land. It’s hard to explain. I’m not going to try. But I think we’ll stay friends for a long, long time.

Imagine getting a call from a friend that goes like this:

“Hey, some guy is visiting from out of town. Will you spend the day taking him around?”

“Who is he?”

“I don’t actually know him. Or know anyone who knows him. He’s a friend of a friend of a friend.”

“Okay. When?”

“Right now?”

“Sure.”

This has never happened in New York’s 399 year history, but it happened in Kampala, Uganda, and it’s how I spent the day with the friend of a friend of a friend of a friend, Sadat, seeing the city.2 He picked me up on his boda boda from my Airbnb on top of the Moonbean Chocolate factory in Bugaloobi and we rode through the green hills towards downtown.

First stop was the vibrant and colorful Nakasero Market. The produce was fresh. Avocados and potatoes were stacked in pyramids on the ground. The merchants were friendly. I bought a mango and a cucumber. I ate the cucumber like a pickle.

We went to an outdoor clothing market where I discovered the horrors of white mannequins. We passed through the old and new taxi parks where hundreds or thousands of drivers wait outside their cars soliciting passengers. Everybody wanted to take me somewhere. North, south, east, west. I was very popular that day.

We toured the beautiful Makerere University, and wandered the grounds of Kabaka's Palace. We found an intense football (soccer) match going on. Sadit had more he wanted to show me but we talked about the value of time and decided we’d better stay and watch through to the end. It was a great match. Super competitive. The crowd was fired up. Music was playing. Everyone was having a good time. The red team won. We ate rolexes for lunch. Ugandan rolexes are omelettes wrapped in chapati. Rolled eggs, rolex. You see? No relation.

I picked up bits and pieces about Uganda and its history. The country is broken up into kingdoms of different ethnic groups. The largest is the Bantu kingdom of Buganda, which is made up of the Baganda people, also known as the Waganda, who speak Luganda. I’m not making this up. Kampala sits within the Buganda kingdom. Uganda is actually named after Buganda, not the other way around. There are at least six other kingdoms. They’ve been around since the 13th century though they’ve played more of a cultural and symbolic role than a ruling one since the late 19th century.

You’ll never believe why. The British showed up. A bunch of explorers who were out searching for the source of the Nile, as the story goes. They liked what they saw, so they summoned the Imperial British East Africa Company who arrived in 1888 and said, “Yes, this is nice. Now it’s ours.” Six years later the British government named Uganda a protectorate, which it remained until it was granted its independence in 1962 as anti-colonial sentiment and resistance swept through East Africa.

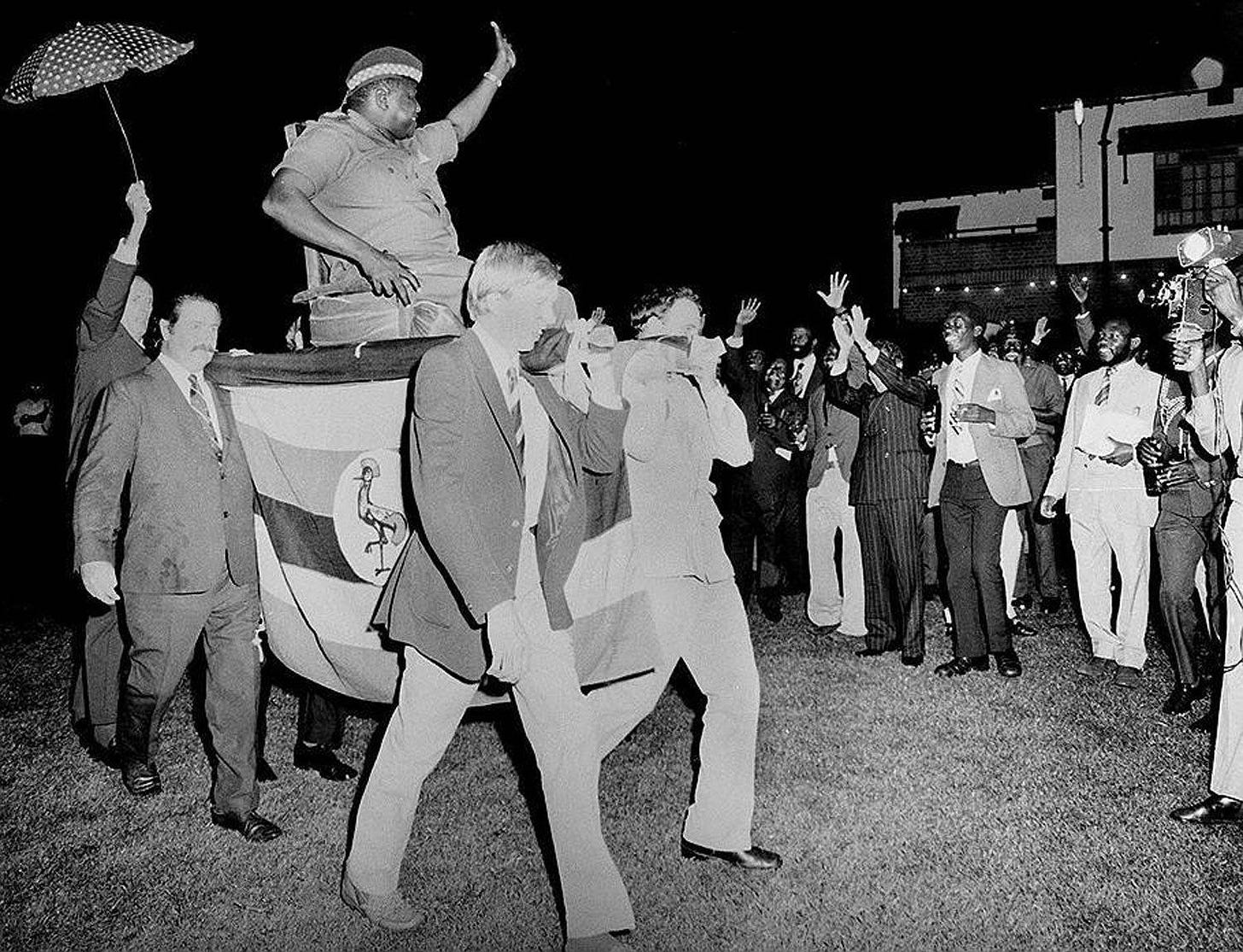

The newly-freed country was led by Milton Obote until he was knocked out of power in 1971 by an Idi Amin-led military coup. Obote had been attempting a Move to the Left which did not sit well with the Brits. Amin, on the other hand, was a former lieutenant of the British Colonial Army who had fought against the Kenyans in the Mau Mau uprising. So he had their support. It didn’t take long for Amin to become a brutal dictator. You may remember him as portrayed by Forest Whitaker in the 2006 film The Last King of Scotland. You may also remember him as the guy who welcomed Air France Flight 139 into Uganda after it was hijacked by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – External Operations in 1976. This led to the famous Entebbe Raid in which 102 of 106 (mostly Israeli) hostages were freed and unit commander (and current Israel Prime Minister Netanyahu’s older brother) Yonatan Netanyahus was killed. Suffice to say, this little whoopsie daisy did not help Amin’s standing in the international community.

Amin’s barbaric reign over Uganda ended in 1979 when he was forced to run off after an ill-advised invasion of Tanzania. This was followed by many years of violent power struggles between different ethnic groups until 1986 when Yoweri Museveni—who studied under Walter Rodney and wrote his thesis on Fanon’s theory of anti-colonial violence— took power. 37 years later, Museveni still rules the country, though there have been countless rebellions and civil wars. Most people agree that the elections have been neither fair nor free, though I couldn’t find anybody willing to take a strong stance on him one way or another. Maybe there is fear, or maybe he is just such a given in Uganda that there’s no obvious reason to have a position. His homophobia is, as you know, well-documented.

The next evening I moved one step up the friend chain and met up with my friend of a friend of a friend, Tonny.

“The boys want to go out tonight,” he said. “How do you feel about that?”

“Very good.”

We met the boys at Mezo, a high-end club in a fancy part of town. The moneyed crowd of Kampala was here. We got a table. Multiple bottles of tequila were ordered. Of course it was Afrobeats all night. Everybody was moving. I was the only white person at the club. Perhaps I stuck out. Sometime around midnight Brian said to me, “You’re trying to follow the beat. Don’t follow the beat, follow my groove.” It was as if God had whispered an absolute truth in my ear. Don’t ask me now what it means.

There was something so breezy about the vibe at Mezo. It felt different. I think what I was noticing was a Black crowd that had no conscious or unconscious worries about the trained gaze of suspicious whites. That’s how it should be, of course, but from my own vantage point, it’s not the norm at the bars and clubs that I go to back home. The night brought to life a reality that I’d been batting around since arriving in Africa—that the experience of Black Americans is entirely unique. Though it also made plain that I spend very little time in predominantly Black spaces in America. For all I know, the Mezo vibe is commonplace. I think it’s probably both.

The next day I met ‘David,’ the LGBT+ activist who I wrote about at length in The Gays of Africa and Those Who’d Like to See Them Gone, and then I joined Tonny and Emmanuel (part of the Mezo crew) for lunch. We ate pork ribs and drank fruity cocktails out of pineapples. I told them about the meeting I’d just come from and asked for their thoughts.

“He sounds very brave,” said Tonny.

“So you don’t have any ill will towards LGBT+ people?”

“No, of course not,” he said.

“No issues at all,” Emmanuel said.

I told them that Uganda typically makes the news in the US for its anti-gay laws or outbreaks of violence.3 They were pretty shocked to hear it.

“What else should we know?” I asked.

“Uganda is one of the most beautiful countries on earth,” Tonny said. “We call it the Pearl of Africa for a reason.”

“We have an extremely diverse population,” Emmanuel added. “And we’re actually a very refugee-friendly country. We take in lots of people fleeing war from South Sudan and the DRC.”

I asked how they felt about Uganda’s relationship with the West.

“I don’t spend too much time thinking about it,” Emmanuel said.

“What about the leftover colonizers?”

“What about them?”

“I see. How about your parents? Do they have strong feelings one way or the other?”

“My parents lived through more civil wars than they can count. They’ve had other things to worry about, like the Lord's Resistance Army abducting children and terrorizing the north.”

“Do you still live with that threat?”

“There is still some violence, especially in the north and the west. There was a terrible attack on a school by the Congolese border just a few months ago.”

“Was that the LRA?”

“No. That was the Allied Democratic Forces. Islamist extremists. The LRA is a Christian extremist group. We have lots of extremists. But all things considered, it’s relatively stable here right now. And I’ll tell you why.”

“Tell me why.”

“There’s nothing left for the West to take from us.”

“What do you mean?”

“Look next door at the Democratic Republic of Congo. The West can’t get enough of their minerals, so the country has been tearing itself apart over control of those mines for as long as it’s existed.”4

“So do you hold the West accountable for the problems you’ve had here?”

“Somewhat. When the Western colonizers left African countries, they didn’t exactly set them up for success. There’s a lot of evidence that the British were involved in Idi Amin’s coup.”

“Us Westerners love supporting a good coup,” I said.

“But you can’t be blamed for everything. And the Westerners I know are good people. Actually I’d love to live in the US one day.”

“How do you picture life in the US?”

“Hm. I think you just live better than us. You have more.”

“Does that make Uganda inferior?”

“No. Of course not.”

“So how do you reconcile those two thoughts?”

“Why do I have to reconcile them? I just make peace with it. It’s not so complicated.”

I went straight from lunch to the airport. I was off to Harare.

I wish I had more to say about Zimbabwe, but my time in the country was spent in two different bubbles. First, with the workshop group in Harare, an amazing experience with some remarkable people, but for better or worse, one spent almost entirely within the confines of a rented house. There was a presidential election coming up and we passed by a large rally—thousands of people lined up at 7am to hear the President speak—but otherwise, I didn’t see much that was noteworthy.5

And the next bubble: the tourist town of Victoria Falls. I’m sure there is some local culture there but I failed to find it. Too tired. I went out on a sunset boat ride on the Zambezi River. I tried telling a family of Spaniards about the volatile sex lives of hippos, but they expressed pure disgust before I could even get to the incel stuff. I knew my trip was coming to an end. The sky turned blood red.

The next day was my final one in Africa. I spent the morning writing at a restaurant that overlooks what must be the most popular watering hole in the savanna. Herds of large animals come and go all day and night. I ate three pastries and drank a full pot of coffee.

I went out to the falls. My goodness. What power this earth holds. I lay down and let myself be overcome by the noise and the wind and the water. ‘The heavens shined down. The light met the blanket of mist floating above the Zambezi River. It scattered across one trillion tiny droplets of water. The wind changed and I felt the cool spray on my forehead.’ I saw a rainbow. I was still.

And then I saw something in the distance that looked off. A blip. I walked along the cliff’s edge until I turned a corner and the view opened up. What the hell. A man was walking a tightrope between Zimbabwe and Zambia, over 300 feet above the Zambezi.6

I sat down and waited for him to make it across.

His name was Laurence. A very sweet South African. He and six others had been planning this stunt for years. The crossing had been done once before, in 2014. I watched Laurence become the tenth person to ever do it.

“I am prepared to be the 11th,” I said.

“I will train you,” Laurence said.

“We have until end of day.”

“I don’t think it’s feasible.”

“Fine. But tell me. What was it like to be out there?”

“It was delightful,” he said. He was rifling through his bag, looking for a piece of chocolate. He smiled when he found it.

“Why do you do it?”

“To connect with nature,” he said. “And to force myself to be present and aware of my body.”

“Were you scared?”

“Sure. But then I told myself I could do it, and I took the first step, and then the next step, and then the step after that.”

“What else were you thinking?”

“How lucky I am to be here!”

I decided to head back to the watering hole for my final hours on the continent. I ordered a glass of wine and a slice of chocolate cake. I tried to be present and aware of my body. The sun began to go down. I don’t know if African sunsets actually present a different palate of colors, but that’s certainly the effect. I drank my wine and ordered another glass. I tried to think about how lucky I was to be there.

And then there was a disruption. People were scurrying around beside me, pointing, and speaking in excited, hushed voices.

There it was, the most magnificent thing I’ve ever seen. A herd of 30 or more elephants emerging from the bush and marching in a single file towards the oasis. They dispersed at the water to drink and bathe. The complex social relations of the herd took shape. The mothers cleaned their young. A baby splashed around and made a ruckus. A giant bull trumpeted and stomped off in indignation. Everybody on the deck was quiet.

They stayed until it was dark and then they assumed formation and marched back the way they’d come. The little ones ran to keep up.

The next day I flew home. I was surrounded by a church group again. Really, I was. But the flight was a pure blackout for me this time around. There were no dreams to speak of. I closed my eyes in Africa and then opened them in New York.

Less than two months after writing that I was heading to Africa because I ‘wanted more,’ I am back in the exact same spot that I wrote those words, seated at my desk in my apartment in Brooklyn, with Dorothy sleeping next to me, drinking coffee from the same old mug. The trappings of my life are unchanged, and there are moments when it feels like I never even left.

But something has changed, undeniably, it’s just hard to make out exactly what. I am exhausted, energized, demoralized, fulfilled, up, down, left, right, 30+ thousand words in and still completely overwhelmed by the sheer volume of raw experience that I’m trying to process.

I’m speaking every day with a number of people I became close with in Africa. Yesterday one of my Nairobi friends shared a karaoke video with the caption A star is born? Kioni and Amara have provided feedback on this piece. I’ve been strategizing with Luke on his tourism business. This morning Ali sent me the story about his father’s death that he’d been working on since the Kibera workshop. The photo that accompanied it struck me right in the heart.

My friends in Kenya have told me that the protests have basically disappeared, and any hope for meaningful change has gone with them (though it may never have existed in the first place). The New Left Review reported on the causes of the protests’ “petering out” as “[1] an elite strategy of divide and rule, with politicians instrumentalizing identity politics to curtail class-based alliances, […] [2] the deep-seated capitalist ethos that courses through the country, making it hard to sustain a solidaristic politics, […and] [3] the precarious position of so many Kenyan workers, [for whom] attending a march means they […] risk going hungry.” The piece goes on, “The opposition coalition and the government are scheduled to enter talks, […] but economic fundamentals are being sidelined – they are just one among several items on an agenda, which gives the impression Kenya’s woes can be solved through simple bureaucratic reorganization. The talks present at most a chance for elite reconciliation.”

It’s disappointing. But people on the ground will tell you that the outcome was entirely predictable. Plus it all sounds very familiar—like a heightened version of the challenges the American Left faces in building a sustained movement.

I do have some regrets about my trip. Of course I wish I’d entered the Nairobi house with a little more diffidence. I wish I’d given myself more time at each stop. I wish I saw the mountain gorillas in Uganda, and that I hadn’t drank the tap water in Kajiado.

And then there are types of people I wish I’d had more opportunities to speak with. Gen-Zers come to mind. Activists, academics and politicians. Also, British people. This may be a weird thing to say about a trip to Africa, but given I spoke with dozens of Black Africans about their feelings towards the British and local white populations, this would have been a good perspective to round things out. Same thing with the affluent.

But my biggest regret is that I made insufficient time to sit quietly and reflect. Maybe I’d have learned some things in the silence.

“The effort that brings a soul to salvation is like the effort of looking or listening.” —Simone Weil

If you, like me, were hoping for some final conclusions around the ethical dilemmas that have arisen during my trip—storytelling versus extraction, engagement versus exploitation, altruism versus saviorism, righteousness versus self-importance, moralism versus relativism, obligation versus humility, resentment versus practicality—I am afraid to tell you that they are not coming.

Only one notion has been crystallized into fact over the past few months: there will never be an ultimate moment of truth. Certainty is ephemeral at best and illusory at worst. My understanding of the world will unfold as an eternal dialectic between my intellectual frameworks and the daily experiences that challenge them. This feels like both an enormous burden and a vast freedom.

On the one hand, I’ll have to keep searching for the rest of my life.

But on the other hand, I’ll get to keep searching for the rest of my life.

So what is it that I want, exactly: ‘more,’ or peace of mind?

Once again, no clear answer. So that’s just how it’s going to be: every day, one step closer to some distant, blurry object.

I can only hope for the occasional lightning flash of clarity. Perhaps, by the time I’m 100, I’ll have been redeemed.

These last two points, which I think about a lot, are paraphrased from Jon Baskin’s “Tired of Winning” in The Point.

Justin (friend)—> Charbel (friend of a friend) —> Tonny (friend of a friend of a friend)—> Sadat (friend of a friend of a friend of a friend).

Last week, a 20-year old man became the first in Uganda to be arrested and charged with ‘aggravated homosexuality,’ which is punishable by death under the country’s new law.

The US and Belgian governments also played a role in the assassination of the DRC’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, for being too Soviet-friendly. An order for the killing came straight from President Dwight Eisenhower himself, though this particular plot was unsuccessful.

From the NYTimes on August 26th: “President Emmerson Mnangagwa won another five-year term, but did so by intimidating voters and manipulating the campaign process, the opposition says.”

More precisely he was walking a ‘slackline.’

I like that all the black Africans you met were like, ‘Chill. Eat snacks. Hang out. Groove. Time is not money but appreciation of the gift of it.’ And then the one white South African you meet (or at least write about) is trying to walk across a tightrope above the Zambezi. I mean… Decolonisation means rest. Rest is resistance. Hang out.

My family had lots of connections to Mombasa. I’m glad it was a lovely moment in time and space for you. Shaista x